What Is Plastic Welding?

Plastic welding is a process used to join plastic materials by applying heat, pressure, or both to create a strong and durable bond. Unlike traditional adhesives or fasteners, plastic welding fuses materials at a molecular level, ensuring a seamless and robust connection. This technique is crucial in industries such as automotive, construction, and manufacturing, where lightweight, durable, and cost-effective components are in high demand.

Understanding Plastic Welding

Plastic welding involves heating the surfaces of two plastic components until they reach their melting point, applying pressure to fuse them, and then allowing the joint to cool and solidify. This method ensures a secure bond by merging the materials into a single unit. Unlike metal welding, plastic welding operates at lower temperatures and focuses on maintaining the integrity of thermoplastic materials.

Types of Plastic Welding

Hot Gas Welding

Hot gas welding is a versatile method that uses a heat gun or torch to direct a stream of hot air onto the surfaces of plastic components and a filler rod, causing them to melt and bond together. The technique is particularly effective for thermoplastics like PVC (polyvinyl chloride), polypropylene, and polyethylene, making it a popular choice for industrial applications.

- Applications: Hot gas welding is frequently used in fabricating and repairing plastic containers, piping systems, and ductwork. It is also utilized in creating custom parts for construction, automotive, and chemical industries.

- Advantages: This method is cost-effective for medium-scale projects and allows precise control over the welding process.

- Challenges: Hot gas welding requires skilled operators to ensure proper heat distribution and avoid overheating, which can weaken the weld.

Ultrasonic Welding

Ultrasonic welding employs high-frequency sound waves (typically in the range of 20 kHz to 40 kHz) to generate localized heat at the joint between two plastic components. The high-frequency vibrations cause the plastic to melt and fuse, forming a strong and precise bond upon cooling.

- Applications: This method is extensively used in the medical device industry for assembling syringes, IV catheters, and surgical tools. It is also critical in electronics manufacturing for components like battery casings and circuit boards.

- Advantages: Ultrasonic welding is fast, efficient, and requires no additional adhesives or filler materials. It is ideal for applications demanding precision and cleanliness.

- Challenges: Equipment for ultrasonic welding can be costly, and the process is typically limited to smaller components with tight tolerances.

Spin Welding

Spin welding is a specialized technique in which one plastic component is rotated at high speed while pressed against another stationary component. The resulting friction generates heat, melting the contact surfaces and creating a solid bond as they cool.

- Applications: Spin welding is commonly used for joining circular or cylindrical components, such as caps, filters, and nozzles.

- Advantages: This method is highly efficient for round components and produces strong, consistent welds without the need for additional materials.

- Challenges: Spin welding is limited to applications with rotational symmetry and may require precise alignment to ensure a quality bond.

Extrusion Welding

Extrusion welding involves the continuous feeding of a molten plastic filler material into the joint while simultaneously applying heat to the plastic surfaces being bonded. The filler material acts as a bridge, enhancing the strength and integrity of the joint.

- Applications: Extrusion welding is widely used in large-scale applications such as fabricating storage tanks, repairing geomembranes, and constructing pipelines.

- Advantages: This method is well-suited for heavy-duty applications and produces welds with excellent mechanical properties.

- Challenges: The process requires specialized equipment and is typically slower than other plastic welding methods. Skilled operators are needed to achieve consistent results.

Heat Sealing

Heat sealing relies on the application of direct heat and pressure to join thermoplastic materials, usually in the form of thin sheets or films. The materials are pressed together while heat is applied, causing them to bond upon cooling.

- Applications: Heat sealing is a staple in the packaging industry, used for creating airtight seals in shrink wraps, blister packs, and food storage bags.

- Advantages: This method is simple, efficient, and suitable for high-volume production lines. It provides a reliable, tamper-proof seal that protects the contents of the package.

- Challenges: Heat sealing is limited to thinner materials and may not be suitable for applications requiring high mechanical strength.

By employing these diverse welding techniques, industries can address specific material and design requirements, ensuring optimal performance and durability in a variety of plastic fabrication projects.

Applications of Plastic Welding

Plastic welding has become an integral process across diverse industries, thanks to its versatility and ability to create durable, lightweight, and cost-effective bonds in thermoplastics. Below are some key sectors where plastic welding plays a vital role:

Automotive Industry

Plastic welding is extensively used in the automotive sector to assemble various components, offering strength and efficiency while reducing weight.

- Dashboard Assemblies: Components such as air vents, instrument panels, and control housings are welded to ensure a seamless finish and robust structure.

- Fuel Tanks: Welded plastic tanks are lightweight, corrosion-resistant, and capable of handling extreme conditions, making them a preferred choice in modern vehicles.

- Bumpers and Body Panels: Automotive bumpers and body panels are often welded to withstand impact and ensure aesthetic integrity.

Medical Industry

The medical industry relies heavily on plastic welding to produce sterile, reliable, and precise products.

- Syringes and IV Bags: Welded plastic ensures leak-proof and contaminant-free assemblies, which are essential for patient safety.

- Surgical Tools: Ultrasonic and laser welding methods are used to create precision joints in medical devices, maintaining high standards of hygiene and functionality.

- Medical Packaging: Sealed plastic packaging for medical instruments and pharmaceuticals is achieved through heat sealing, providing a sterile barrier.

Packaging Industry

Plastic welding is indispensable in the packaging industry for creating secure, durable, and visually appealing packaging solutions.

- Blister Packs: Welded plastic packs are commonly used for electronics, pharmaceuticals, and consumer goods, offering protection and product visibility.

- Shrink Wraps: Heat sealing in shrink wraps ensures airtight protection for perishable items like food and beverages.

- Food Containers: Plastic welding creates leak-proof seals in food storage containers, ensuring freshness and extending shelf life.

Construction Industry

In construction, plastic welding contributes to durable and long-lasting infrastructure components.

- Piping Systems: Welding techniques like extrusion welding are employed to create strong, leak-resistant joints in PVC, HDPE, and polypropylene pipes.

- Roofing Membranes: Plastic welding is used to bond thermoplastic membranes for waterproofing and insulation in roofing applications.

- Geosynthetic Linings: Welded plastic liners are essential for landfills, reservoirs, and tunnels to prevent leakage and environmental contamination.

Consumer Goods Industry

Plastic welding is widely utilized in manufacturing a variety of consumer goods to improve functionality, aesthetics, and durability.

- Toys: Welded plastic ensures durability and safety in children’s toys, enabling precise and robust designs.

- Electronics: Products like smartphones, laptops, and appliances often incorporate welded plastic casings to protect delicate internal components and provide a sleek appearance.

- Appliances: From washing machines to vacuum cleaners, plastic welding is used to assemble various parts, ensuring efficiency and reliability.

By tailoring plastic welding techniques to the specific needs of each industry, manufacturers achieve high-quality results while optimizing cost, weight, and durability. This versatility makes plastic welding an essential process across modern manufacturing and industrial applications.

Materials Suitable for Plastic Welding

Plastic welding is most effective with thermoplastics—materials that soften when heated and harden upon cooling, making them ideal for welding processes. These plastics can be repeatedly melted and reformed, enabling strong, durable bonds. The suitability of a material for plastic welding depends on factors such as its melting temperature, chemical composition, and physical properties.

Common Thermoplastics for Plastic Welding

- Polyethylene (PE)

- Properties: Lightweight, durable, and highly resistant to chemicals and moisture.

- Applications: Commonly used in piping, tanks, containers, and geomembranes. Its weldability makes it a favorite in industrial and construction settings.

- Polypropylene (PP)

- Properties: High resistance to fatigue, excellent chemical resistance, and low density.

- Applications: Frequently used in automotive components, medical devices, and consumer goods. Its ease of welding makes it ideal for creating intricate designs and strong joints.

- Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC)

- Properties: Stiff, strong, and resistant to corrosion and weathering.

- Applications: Widely employed in plumbing, electrical conduit, and signage. PVC welding is popular for creating leak-proof joints in piping systems.

- Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene (ABS)

- Properties: Tough and impact-resistant, with good dimensional stability.

- Applications: Commonly used in automotive interiors, toys, and electronic housings. ABS welding is favored for its ability to produce smooth and durable seams.

- Polycarbonate (PC)

- Properties: High impact strength, transparency, and resistance to heat.

- Applications: Often used in medical equipment, optical lenses, and construction materials. PC welding ensures strong bonds without compromising its clarity or durability.

- Nylon (Polyamide)

- Properties: Excellent mechanical strength, wear resistance, and low friction.

- Applications: Found in gears, bearings, and industrial components. Nylon welding requires precise control of heat to avoid material degradation.

Factors Influencing Weldability

- Melting Temperature

- Thermoplastics with a narrow melting temperature range are easier to weld. Excessive heat can degrade the material, while insufficient heat can lead to weak bonds.

- Chemical Composition

- The chemical structure of the plastic affects its ability to fuse. For instance, polar plastics like PVC and ABS weld more easily than non-polar plastics like polyethylene, which may require special surface treatments.

- Material Thickness

- Thicker materials require more heat and time to achieve proper fusion, while thinner materials demand precise control to prevent warping or burn-through.

- Compatibility

- Only similar thermoplastics can be effectively welded together. Attempting to weld dissimilar plastics often results in poor adhesion or joint failure due to differences in melting points and chemical properties.

Unsuitable Materials: Thermosetting Plastics

Thermosetting plastics, such as epoxy, bakelite, and melamine, are not suitable for plastic welding. These materials undergo a chemical change during their initial curing process, making them unable to soften or re-melt when reheated. Instead, they char or degrade under high temperatures, rendering welding techniques ineffective. Alternative joining methods, like adhesives or mechanical fasteners, are typically used for thermosetting plastics.

Specialized Materials

- Composite Materials

- Certain composites containing thermoplastic matrices can be welded, provided the reinforcement materials (e.g., fibers) do not interfere with the process.

- Modified Plastics

- Plastics enhanced with additives for improved properties (e.g., UV resistance or flame retardancy) may still be weldable, but their behavior during welding should be carefully assessed.

By understanding the properties and behaviors of different plastics, manufacturers can select the right material and welding method for their applications. This ensures high-quality results and durable bonds, even in demanding environments.

Advantages of Plastic Welding

Lightweight and Durable Bonds

Plastic welding creates robust and lightweight connections, making it ideal for industries like automotive, aerospace, and consumer goods. The process ensures high strength while maintaining the material’s inherent lightweight properties. This combination of strength and minimal weight is crucial for improving product performance and efficiency, particularly in applications such as vehicle components and portable electronics.

Cost-Effectiveness

Plastic welding is a cost-efficient joining technique, especially in large-scale or high-volume manufacturing. Unlike mechanical fasteners or adhesives, welding eliminates the need for additional materials, such as screws or glue, reducing overall production costs. Furthermore, the process is often faster than alternative methods, leading to increased productivity and lower labor expenses.

Repair and Sustainability

Plastic welding supports the repair of damaged plastic parts, offering a practical solution to extend the lifespan of products. This repair capability reduces the need for replacements, saving resources and cutting down on waste. Additionally, plastic welding aligns with sustainable practices by enabling the recycling of thermoplastic materials, contributing to a circular economy where materials can be reused instead of discarded.

These advantages make plastic welding a versatile and valuable technique in modern manufacturing and maintenance processes.

Challenges and Considerations

Material Compatibility

One of the most significant challenges in plastic welding is ensuring material compatibility. Not all plastics can be effectively welded together, as the process relies on the materials having similar melting points and chemical properties. For example, thermoplastics such as polyethylene and polypropylene are ideal for welding, while thermosetting plastics, which cannot be remelted, are unsuitable. Using incompatible materials can result in weak or brittle joints, reducing the integrity and durability of the finished product. Proper material selection and testing are essential to ensure a successful weld.

Precise Parameter Control

The quality of a plastic weld is heavily dependent on controlling key parameters such as temperature, pressure, and cooling time. Overheating can degrade the plastic, causing it to lose strength or create burn marks, while insufficient heat may prevent the materials from bonding effectively. Similarly, applying too much or too little pressure can result in uneven joints or gaps. Cooling time must also be optimized to prevent warping or stress within the material. Achieving the correct balance of these factors requires careful monitoring and precision, often with the help of automated systems in industrial applications.

Equipment and Skill Requirements

Plastic welding often requires specialized equipment tailored to the specific welding technique, such as hot gas welders, ultrasonic welders, or extrusion welders. These machines can represent a significant upfront investment, particularly for high-quality or high-capacity models. Additionally, operators must have the necessary training and experience to handle the equipment, adjust parameters, and ensure consistent weld quality. This reliance on skilled labor and advanced machinery can increase operational costs and pose a barrier for smaller businesses or those new to the process.

Addressing these challenges involves thorough preparation, investment in the right tools and training, and a clear understanding of the materials and techniques involved. While these considerations can make plastic welding demanding, they are essential for achieving reliable and durable results.

Best Practices for Plastic Welding

Surface Preparation

Proper surface preparation is fundamental to achieving strong and durable plastic welds. Contaminants like dirt, grease, oils, and moisture can weaken the bond or create voids within the joint. Before welding, surfaces should be cleaned with an appropriate solvent or cleaning agent that won’t degrade the plastic material. For certain applications, mechanical preparation like light sanding or abrasion may be used to improve adhesion by creating a slightly roughened surface. Ensuring that the surfaces are dry and free of debris is essential to maximize weld strength.

Technique Selection

Selecting the appropriate welding method is critical for achieving the desired results. The choice depends on several factors, including the type of plastic, material thickness, and the intended application. For instance:

- Hot Gas Welding is ideal for thermoplastics in industrial applications such as tanks and piping.

- Ultrasonic Welding is suited for precision tasks in industries like medical devices and electronics.

- Spin Welding works well for circular components, offering reliable bonds for caps or filters.

- Heat Sealing is preferred for thin films in packaging applications.

Matching the technique to the material properties and project requirements ensures efficiency and long-lasting welds.

Monitoring Critical Parameters

Consistent control over key welding parameters—temperature, pressure, and weld time—is essential for producing reliable joints.

- Temperature: The correct heat setting prevents material degradation from excessive temperatures or insufficient bonding due to underheating. Different plastics require specific temperature ranges for optimal melting.

- Pressure: Applying the right amount of pressure ensures even fusion without causing deformation or gaps. Too much pressure can squeeze out molten material, while too little can result in weak bonds.

- Weld Time: Maintaining precise weld durations allows the material to properly melt and fuse while preventing overheating or incomplete bonding.

Modern welding machines often incorporate automated systems to monitor and adjust these parameters in real-time, reducing the likelihood of errors and ensuring consistency.

Consistent Quality Checks

Performing regular inspections during and after the welding process is critical. Visual checks can identify surface imperfections, while non-destructive testing methods like ultrasonic testing or tensile strength tests can confirm the internal integrity of the weld. Implementing quality assurance protocols ensures that each weld meets the required standards for strength and durability.

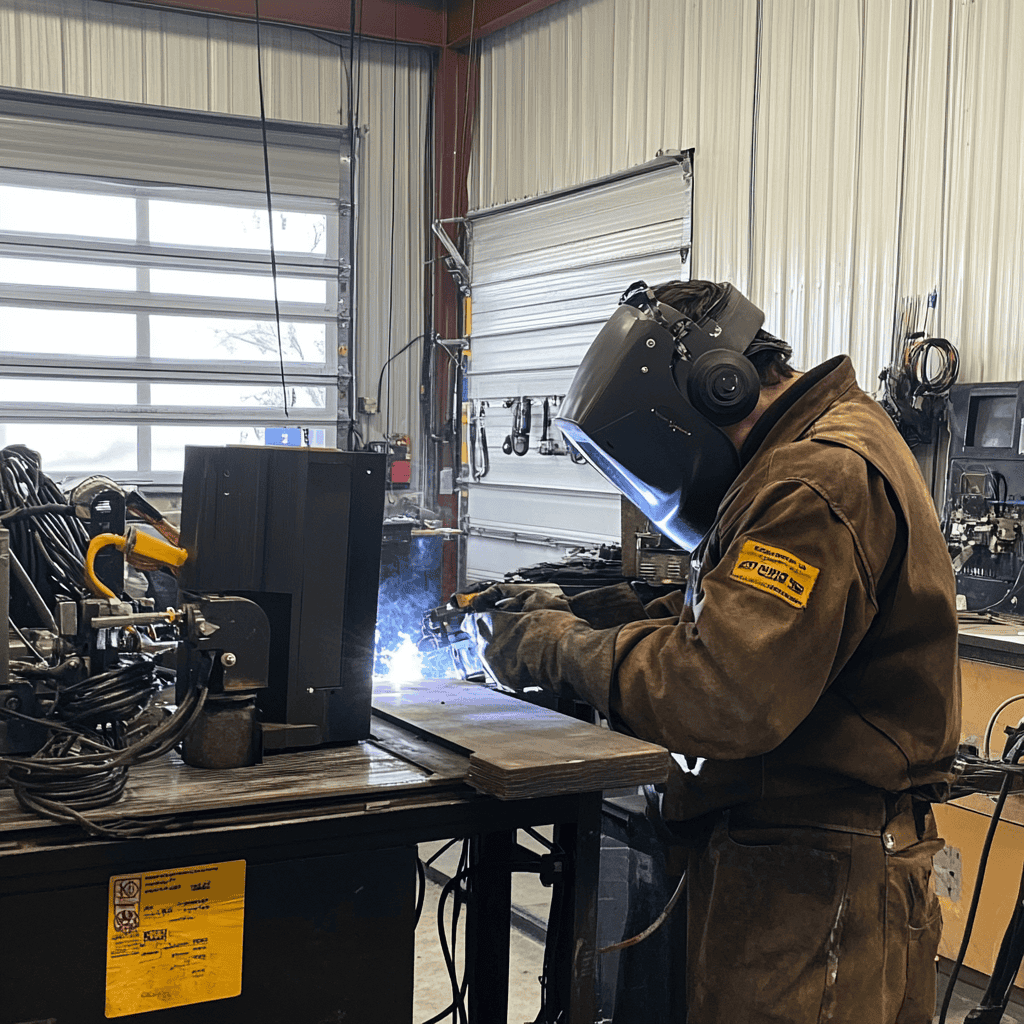

Safety Measures

Plastic welding involves heat, pressure, and potentially harmful fumes, making safety precautions essential. Operators should wear appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE), such as gloves, goggles, and face masks, to minimize risks. Proper ventilation is crucial, particularly when welding materials that release fumes, such as PVC. Following these safety guidelines not only protects workers but also ensures a smoother welding process.

By adhering to these best practices, welders can maximize the effectiveness and reliability of plastic welding, delivering strong, durable bonds suited to a variety of industrial and commercial applications.

Conclusion

Plastic welding is a versatile and effective technique for joining thermoplastic materials in various industries. By providing strong, lightweight, and cost-efficient solutions, it has become an essential part of modern manufacturing and construction. As advancements in plastic welding technology continue, its applications are expected to expand, offering even greater possibilities for innovation and efficiency.

Additional Resources

Get your welding gear here.